How the Devils are Attempting to Revolutionize the Power Play

The New Jersey Devils are trying something a little different on the power play this season, and it may very well be the beginning of a new era of power play operations around the NHL.

With the regular season having just started, I have tons of exciting plans for this Substack and can’t wait to share them with you all! To support me and my work, please consider subscribing to the page — it’s free of charge, and it helps with the algorithm quite a bit. If you’re subscribed already, consider sharing this with friends, family, and any hockey fans you know to keep them up to date with quasi-daily, in-depth Devils content! Thank you!

Thank you to Discord user dml2662 for this topic suggestion!

Last season, the Devils brought on former Blackhawks head coach Jeremy Colliton as the final addition to New Jersey’s coaching staff under the expectation that he would be the engineer of the team’s power play. To that extent, outside of a miserable Round One series against the uber-aggressive Carolina Hurricanes, his endeavors and system were an overwhelming success.

The machinations of 2024-25’s power play were incredible to watch when the team was operating at its best. The constant positional fluidity and rotations kept defenses on their feet, resulting in a greatest-of-all-time expected goal production for the regular season.1 When their movement stagnated — in the playoffs — their system floundered and they went 0-for-16.

Flash forward to the beginning of 2025-26, and the Devils are once again changing the expectations around how a power play operates. On top of the aforementioned positional fluidity — the Devils’ flanks and bumper positions are in constant rotation with each other on their first unit, with even the flanks rotating with the quarterback depending on the situation — they’re trying something unorthodox personnel-wise: changing the first unit depending on the system and team that is playing against them.

Sheldon Keefe made a comment recently about the systemic change there, and as far as I can recall, I don’t think any other NHL team has ever done this, or at least been so open about the strategy.

So, through the first four games of the season — which is undoubtedly a minuscule sample size — what have we seen so far, and when will the personnel changes occur?

The Combinations

Though the season is four games young, the Devils’ first unit has seen a surprising amount of iterations already.

Being that Stefan Noesen has begun the season on injured reserve, though he is expected back soon, the Devils’ initial first power play consisted of the typical three forwards — Jack Hughes and Jesper Bratt on the flanks and Nico Hischier occupying the bumper — with Dawson Mercer as the netfront presence and semi-newly-extended Luke Hughes quarterbacking the unit.

From that point in time, we’ve seen two other versions of the first power-play unit:

Jack Hughes - Jesper Bratt - Nico Hischier - Timo Meier - Luke Hughes

Jack Hughes - Jesper Bratt - Nico Hischier - Timo Meier - Dougie Hamilton

Under these units, Hischier has moved to being the netfront presence, with J. Hughes, Meier, and Bratt floating between the flank and bumper positions (and occasionally rotating with L. Hughes or Hamilton).

I’m not going to get into the results of the different groups just yet, simply because the sample sizes of each unit are exorbitantly small, though that is something I do intend on doing later on in the season.

With Stefan Noesen’s return imminent, I can only imagine that, considering the success of the team’s power play with him on it last season, he will be a factor in these units once he becomes active on the roster. Considering that J. Hughes, Bratt, and Hischier are staples on the first unit — as they should be — I would guess that he would rotate with Meier and operate as the netfront chaos agent he was last season.

Deployment

In today’s NHL, power plays are much more complex in their systems than penalty kills. To be fair, there’s only so much you can do with a four-man, exclusively-defense operation, but there is a reason why power plays have become much more lethal in recent history, and it’s because the far more complex systems have been architected to manipulate and break down the penalty killing schemes that have largely remained unchanged.

As far as penalty kills go, there are only a few different layouts:

2-2 box: Probably the most common of the options. The four-man group organizes itself into a box formation, with two forwards up top to pressure the quarterback/flanks and compress when the puck becomes more central to the offensive zone. Two defenseman down-low to prevent high-danger, cross-crease passes and compress to block shots from the perimeter.

1-2-1 diamond: A more aggressive version of the 2-2 box that is shifted 45 degrees. This allows power plays to get more outnumbered situations down low, but almost always has aggressive puck pursuit by the defenders that try and force turnovers or bad plays by their unending pressure.

1-1-2 wedge: Only a couple of teams use this system, which is generally pretty effective against the typical 1-3-1 power-play setup. The F1 in this case is responsible for pressuring the point and flanks on short-distance passes, with the defenseman on either side moving slightly toward the perimeter to deny a passing lane to the player operating near the goal line. This leaves the other defenseman responsible for covering the bumper player and the opposite-side flanker. This system is effective against 1-3-1s that don’t have the advanced movement that the Devils employ or passers like Nikita Kucherov and Connor McDavid, who can find the smallest of seams to thread passes through.

Under these three systems, penalty kills also employ one of two mentalities: aggressive or passive.

1-2-1s are almost always aggressive, with hard pressure applied by whoever is closest to the puck carrier. 1-1-2s are typically pretty passive, though the pressure applied at the point is most prominent. 2-2 box formations can go either way.

In a passive box system, while the puck carrier is usually slightly pressured by a defender one full stick-length away, the reliance is much more on the formation maintaining its structure than forcing the opposition into a bad play or turnover. In an aggressive box, ones like the Carolina Hurricanes and Devils use, it almost turns into man-to-man+1 coverage. This forces a ton of turnovers and odd-man rushes the other way, which is why those teams are often at the forefront of short-handed goals, and if not goals, opportunities.

With all that in mind, the Devils can, and have, approached different systems with different ideologies.

With an aggressive system, the Devils have either the option of 1) leaning into the aggression and putting five puck-protection-heavy players to avoid turnovers altogether, or 2) using a shot-heavy quarterback (Hamilton) to force the penalty killers into staying back a little bit instead of being as aggressive as usual, because of the threat of the point shot.

The Devils are lucky enough to employ one of the best point-shot threats in the NHL in Hamilton, whose one-timer is only rivaled by the likes of Evan Bouchard and Victor Hedman. With that comes the forced fear that is instilled in the opposition, compelling the penalty killers into backing off and respecting the shot. This also has an effect on the opposing netminders, but this is more about the skaters.

The other school of thought is to deploy five puck-possession-oriented players who can each facilitate the puck at a high level. In this case, L. Hughes would be the quarterback, as he is able to absorb the pressure, outmaneuver it, and dish the puck off to someone else as a byproduct of his otherworldly skating ability.

Surprisingly enough, we saw both in the Devils’ home opener.

The Panthers, against the Devils, used an aggressive 1-2-1 diamond formation. During their first few power plays, they deployed the typical four forwards (J. Hughes, Bratt, Hischier, Meier) with L. Hughes as the quarterback. With this, the Panthers pressured to no avail, with the Devils’ star players being able to avoid turnovers and keep possession alive through quite a few aggressive plays by the pressing defenders:

In the above sequences, you can see the Panthers apply significant amounts of pressure to both of the Hughes brothers and Jesper Bratt. In the first sequence, L. Hughes was given a heavy dose of stick checks and physical pressure at the point two times, and his brother was given the same treatment on the flank twice. Both players are evasive enough and intelligent enough to escape the applied pressure, which ended up opening a passing lane to Hischier (who swapped positions with Meier while the attention was given to the Hughes brothers) in the bumper and an additional chance by an uncovered Meier at the netfront. In the second sequence, pressure is slightly applied to Bratt from a tired Panthers group, and he is able to exploit their attention to him and exhaustion by setting up an in-motion Hischier, who subsequently tries a back-door pass to a streaking J. Hughes.

Later on in the same game, directly after a minute-long 4-on-3 man-advantage, the Devils further took advantage of exhaustion and the passivity that comes along with it by sending Hamilton out to quarterback the power play instead of L. Hughes. In doing so, the Devils were able to effectively use No. 7’s shot from the point to generate chances that otherwise would have been less threatening:

Pressure was still applied to J. Hughes in the above clip, but there was significantly more sitting back once the puck was passed to the point. In my opinion, this was a byproduct of Mackie Samoskevich (No. 11 on the Panthers, who had just come out of the box prior to this clip) sitting back out of respect for Hamilton’s shot and the passivity of the other members of the group. The Devils were able to identify that they could exploit the defenders’ fatigue with the four forwards already out there, and sent out Hamilton for a shooting threat that otherwise would have been less effective.

In the game before that, the Devils played against the Columbus Blue Jackets, who typically employed a 1-2-1 last season and have done the same in the early goings of this season. Against them, Keefe and Colliton sent out Hamilton, who I anticipate was brought out because they knew that the four forwards would be able to manipulate and puck-protect enough to open up some shooting opportunities for the veteran blueliner.

Initially, because of the wide swing taken by Blue Jackets’ No. 24 (Mathieu Olivier), it appears as though this was a box formation, though this was just a miscalculation by Olivier. Once Bratt passed the puck to Meier, who traversed behind the net, the diamond formation collapsed with the intention of limiting a pass to the flanking players (Bratt and J. Hughes). Meier identified this sudden gap in coverage and exploited it by passing to a now-open Hamilton, whose shot created a small bit of chaos and havoc, leading to a defensive breakdown in coverage and an eventual goal by Meier.

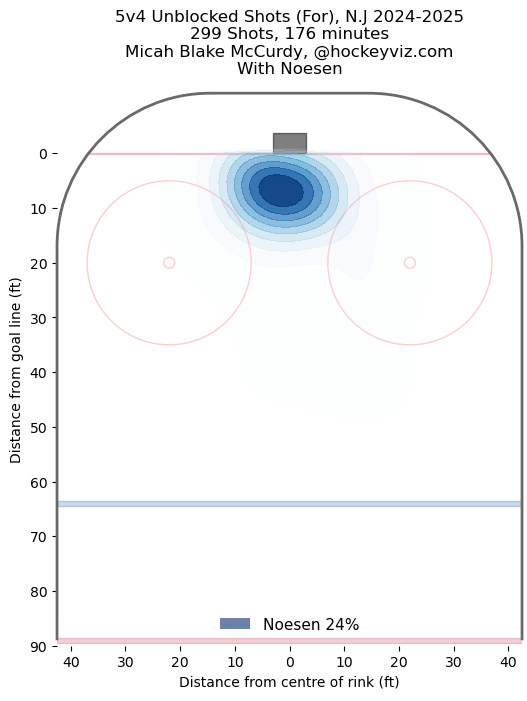

The Devils haven’t played against a passive system quite yet, as we’re still only four games into the season, and aggressive PKs are much more common. Despite that, in my opinion, there are again two schools of thought: 1) use five puck-dominant players who can manipulate the defense into drawing coverage to themselves, opening up potential passing and shooting lanes that otherwise wouldn’t be there, or 2) lean into their passivity by utilizing Hamilton’s shot from the point and creating as much chaos as possible. With option #2, I have to imagine it would be more effective with Noesen as the netfront presence, as his impact on the Devils’ power play last season simply cannot be denied as that previously mentioned chaos agent. You can see the heat map of his shots on the power play below, and why I think it would be important to use him if that is the approach the Devils take against structured PK units:

All in all, the overarching theme here is that the Devils might be on the precipice of changing how the NHL operates on power plays, depending on the success level of their season-long endeavors on the man-advantage. The training wheels were certainly on for their first couple of games, but now that they’re getting more comfortable in their approach against different teams, I believe we’re seeing how dominant they can be — they have three power-play goals in their last two games.

As far as I’m aware, there isn’t another team in the league that uses this sort of creativity on the power play — from what I’ve seen, all clubs tend to utilize the same players on the power play regardless of situation and teach their players how to play against different defensive schemes rather than play into the individual strengths of the players themselves. Colliton’s power play was already fluid and creative for its constant rotations, but they’re seemingly taking it up a notch in 2025-26.

As much as this might seem like an exaggeration, it isn’t.

Since expected goals (xG) started getting tracked in 2007-08, only seven teams have surpassed the 10.00 expected goals per 60 minutes (xGF/60) threshold on the man-advantage. In 2010-11, it was the San Jose Sharks (10.29 xGF/60). The Edmonton Oilers were the next team to accomplish the feat in 2022-23 (10.19), and three teams executed it in 2023-24: Minnesota (10.68), Florida (10.28), and Edmonton once again (10.14). Both the Pittsburgh Penguins and New Jersey Devils crossed that threshold in 2024-25, with the Penguins sporting an xGF/60 of 10.09 and the Devils sporting the highest mark of any team ever recorded with a 10.85.

On top of that, the Devils’ 2024-25 power play recorded the fifth-most high-danger chances per 60 (HDCF/60) mark of all-time (33.45) and the most scoring chances per 60 minutes (SCF/60) of all-time (77.41).

Things get much crazier when taking into account the personnel. Prior to the injury to Jack Hughes, the Devils’ first power play unit consisted of him, Dougie Hamilton, Nico Hischier, Stefan Noesen, and Jesper Bratt. With those five players on the ice for the power play, which was a staple for the 52 games that all five players were healthy, the group was generating a ridiculously mind-boggling 15.15 xGF/60, 41.16 HDCF/60, and 92.59 SCF/60, all of which would have destroyed any prior NHL record.

In many ways, despite their power play only ending up third-best in 2024-25, the Devils’ 2024-25 season can be regarded as the greatest statistical power play performance of all time.